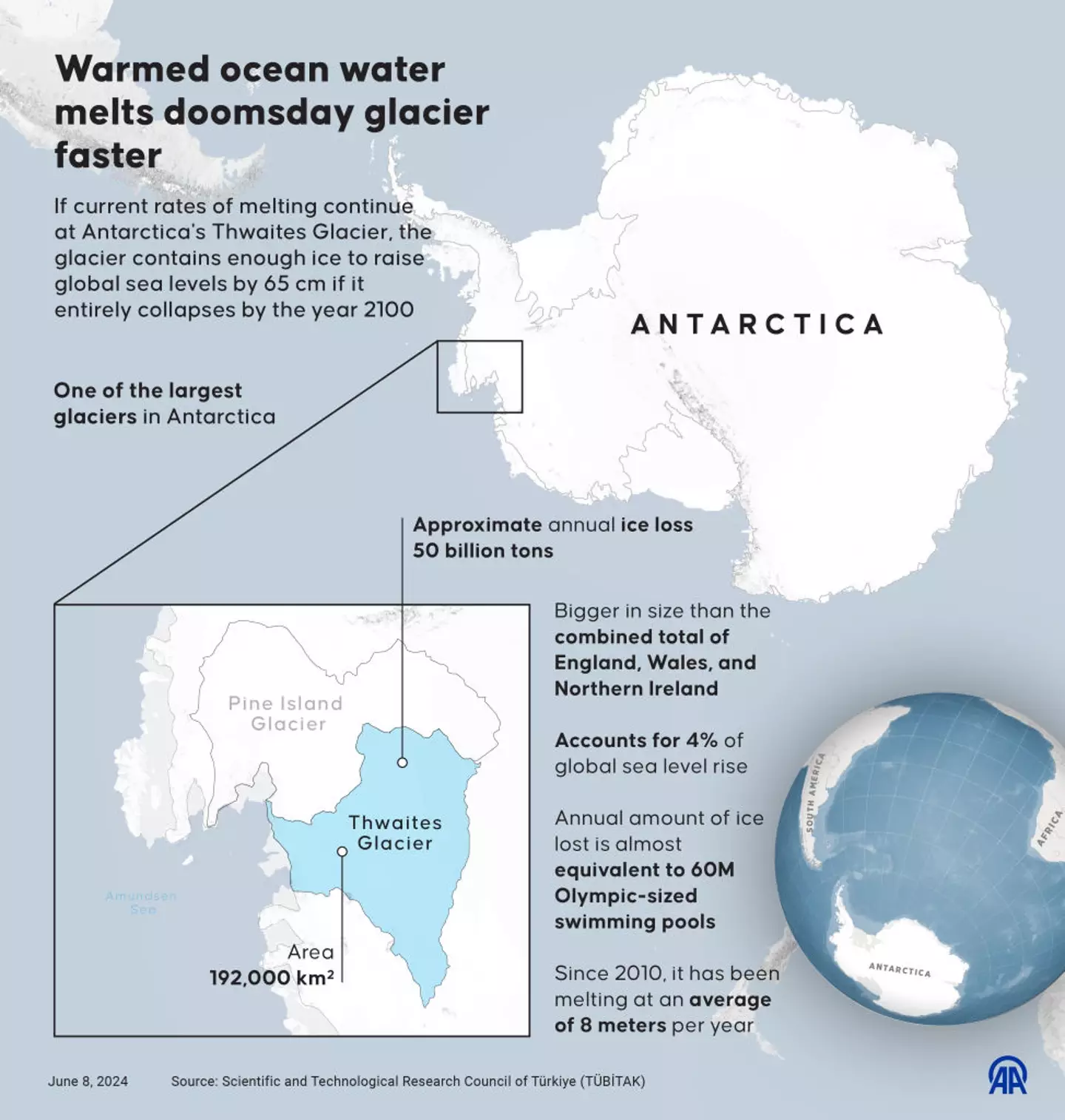

Scientists have warned that the Thwaites Glacier in West Antartica – a slab of ice around the size of Great Britain – is continuing to retreat.

Earth’s temperature has risen by an average of 0.11F per decade since 1850, and global warming appears to be taking its toll.

Combined with the wider region, the Thwaites Glacier accounts for eight percent of the current rate of global sea level rise of 4.6mm a year.

Latest predictions are now saying that major or complete ice loss of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could take place in the 23rd century.

Urgent action is now needed to help slow this process down, experts have said.

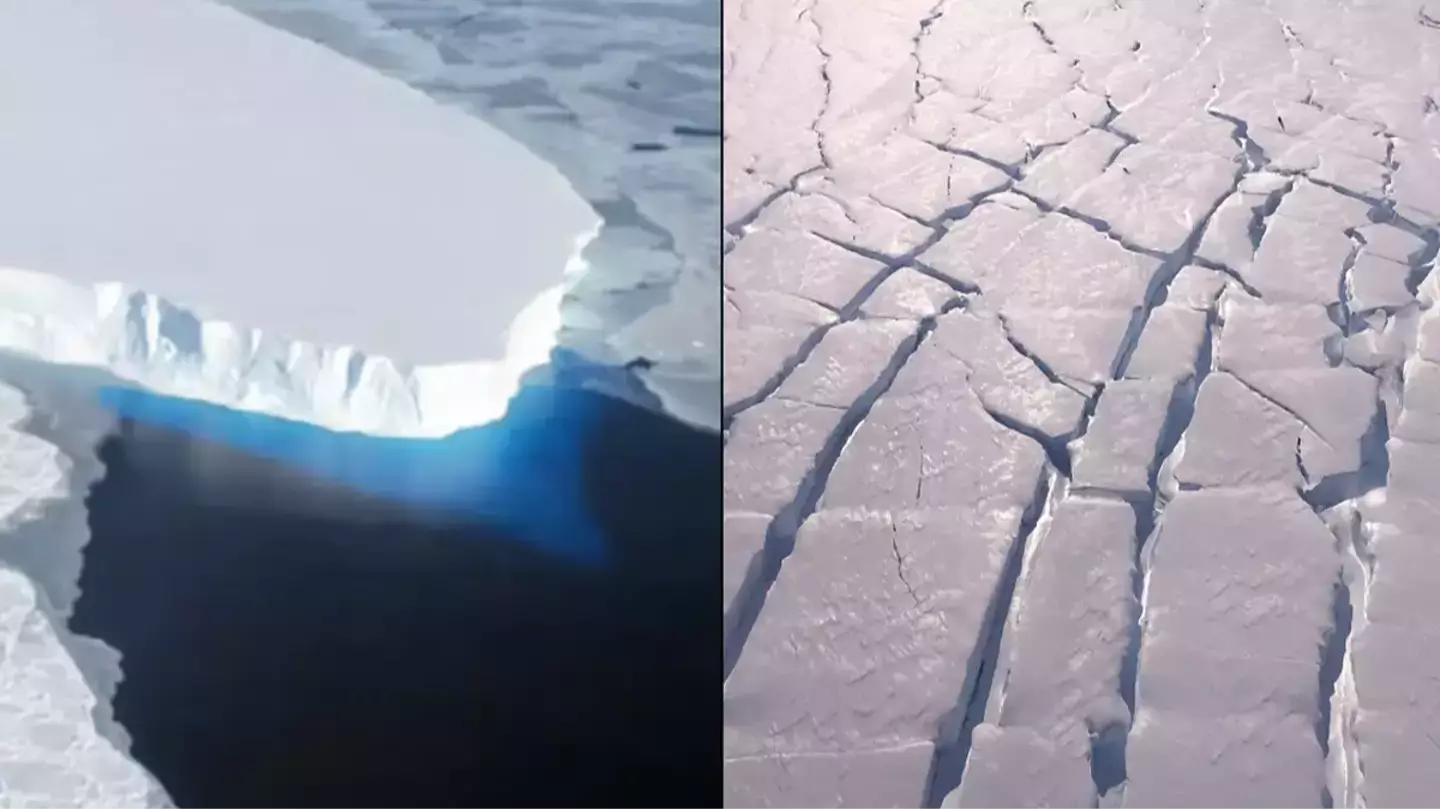

If the ‘Doomsday Glacier’ collapsed entirely, sea levels would rise by 65cm (Getty Stock Image)

Scientists from the UK and US are now planning to meet at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) in Cambridge to discuss their observations this week.

Researchers are set to use a combination of underwater robots and new techniques to see if they can learn more about the future of the ‘Doomsday Glacier’.

Sea levels would raise by 3.3 metres if it all melted and would cause world-wide flooding, loss of habitat, and an increase in the number of storms.

In the UK alone, the likes of Hull, Peterborough, Portsmouth and parts of east London and the Thames Estuary would be at risk of being submerged in water.

Dr Rob Larter, from the Science Co-ordination of the ITGC and a marine geophysicist at BAS, said: “Thwaites has been retreating for more than 80 years, accelerating considerably over the past 30 years.

“And our findings indicate it is set to retreat further and faster.

Experts have issued another terrifying update on the ‘Doomsday Glacier’ (Yasin Demirci/Anadolu via Getty Images)

“There is a consensus that Thwaites Glacier retreat will accelerate sometime within the next century.

“However, there is also concern that additional processes revealed by recent studies, which are not yet well enough studied to be incorporated into large-scale models, could cause retreat to accelerate sooner.”

Dr Ted Scambos, US science co-ordinator of the ITGC and glaciologist at the University of Colorado, added: “It’s concerning that the latest computer models predict continuing ice loss that will accelerate through the 22nd century and could lead to a widespread collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in the 23rd.

“Immediate and sustained climate intervention will have a positive effect, but a delayed one, particularly in moderating the delivery of warm deep ocean water that is the main driver of retreat.”

In Antarctica, there’s something known as the Thwaites Glacier, though we’d rather use its far more impressive sounding nickname the ‘Doomsday Glacier’.

The reason it has such a dramatic moniker is because it’s part of what’s been described as the ‘weak underbelly’ of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, where it’s vulnerable to collapse and if it goes it’ll probably take the whole ice sheet with it.

This glacier and another one, called the Pine Island Glacier, are believed to be very likely to collapse without much warning in the future.

The consequences of this glacier’s collapse could be a significant rise in sea levels, which would destroy many coastal towns and cities resulting in millions of people losing their homes.

While that’s the bad news, and it would be pretty bad if and when it happened, the good news is that scientists who are regularly monitoring the glacier say the worst-case scenario is currently unlikely.

The Thwaites glacier in Antarctica, sometimes known as the ‘Doomsday Glacier’. (NASA)

A new study into the sturdiness of the glacier suggests that one of the biggest risks, that of marine cliff ice instability (MICI), may not be a concern throughout the 21st century.

Professor Mathieu Morlighem wrote in The Conversation that when an ice shelf collapses it exposes tall cliffs of ice, and the taller they are the tougher time they have holding things together.

Fortunately, this new study indicates that the glacier ‘remain fairly stable at least through 2100’, and when they simulated a possible collapse in 50 years time, the cliffs wouldn’t be high enough to rapidly collapse.

If you’re wondering what this all means for the ‘Doomsday Glacier’ and our planet it’s good news – for now, at least.

The rapid collapse that would represent a ‘nightmare scenario’ is even more unlikely than before reports USA Today, and professor Morlighem told them that even though the glacier and ice sheet were still in retreat, it would go ‘not as rapidly as one scenario suggested’.

.jpg)

The more the ice melts the higher our sea levels will rise. (Sebnem Coskun/Anadolu via Getty Images)

By the end of the century, sea levels are already expected to rise by about two to three feet.

The nightmare scenario which we can expect to avoid would have eventually resulted in a 50ft rise in sea levels that would have been devastating.

Professor Morlighem was keen to stress that this study’s findings ‘doesn’t mean Thwaites is stable’.

The ‘Doomsday Glacier’ likely not being about to collapse is a nice update – what’s less nice is that it is still melting and losing mass.

Even though the Antarctic is very cold, ocean currents carrying warmer water are thinning the ice from underneath and you can’t just go and get a new massive glacier to replace what’s being lost.

The Thwaites Glacier has the potential to be catastrophic for coastal communities worldwide as scientists have a fresh and worrying update for us.

Located in West Antartica is the ginormous slab of floating ice – around the size of Great Britain – which remains in rapid retreat.

After using data from Finland’s ICEYE commercial satellite mission from March to June of 2023, they concluded that there might need to be a reassessment of global sea level projections.

The glacier has the potential to increase global sea levels to more than two feet if it melts completely, according to the study.

This find lead to flooding, loss of habitat, and increase in the number of storms.

Co-author Christine Dow, professor in the Faculty of Environment at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada, told the University of California, Irvine: “Thwaites is the most unstable place in the Antarctic and contains the equivalent of 60 centimetres of sea level rise.

“The worry is that we are underestimating the speed that the glacier is changing, which would be devastating for coastal communities around the world.”

The Thwaites Glacier is around the size of the UK. (James Yungel/NASA)

“These ICEYE data provided a long-time series of daily observations closely conforming to tidal cycles,” lead author Eric Rignot, UC Irvine professor of Earth system science, added.

“In the past, we had some sporadically available data, and with just those few observations it was hard to figure out what was happening.

“When we have a continuous time series and compare that with the tidal cycle, we see the seawater coming in at high tide and receding and sometimes going farther up underneath the glacier and getting trapped.

“Thanks to ICEYE, we’re beginning to witness this tidal dynamic for the first time.

“There are places where the water is almost at the pressure of the overlying ice, so just a little more pressure is needed to push up the ice.

“The water is then squeezed enough to jack up a column of more than half a mile of ice.”

The West Antartica glacier remains in rapid retreat. (IceBridge/PA)

ICEYE Director of Analytics, Michael Wollersheim, credited the readily available resources and said: “Until now, some of the most dynamic processes in nature have been impossible to observe with sufficient detail or frequency to allow us to understand and model them.

“Observing these processes from space and using radar satellite images, which provide centimeter-level precision InSAR measurements at daily frequency, marks a significant leap forward.”

.png)

The clock shows us just how close humanity is to suffering global catastrophe, caused by ourselves.

Setting the Doomsday Clock every year is the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (BAS).

Their purpose is to ‘equip the public, policymakers, and scientists with the information needed to reduce man-made threats to our existence’. The closer we are to midnight, the more at risk we are.

Last year, the clock was set at a worrying 90 seconds to midnight following Russia’s war on Ukraine. The conflict continues to this day.

BAS met this afternoon (23 January) to give their 2024 update on the clock and how at risk humanity was from a catastrophic event.

Making the announcement was Rachel Bronson, PhD, president and CEO of BAS.

Getty stock photo

Setting the groundwork before making the announcement, Dr Bronson told the virtual conference: “Countries with nuclear weapons are engaged in modernisation programmes that threaten to create a new nuclear arms race.

“Earth experienced its hottest year on record and massive floods, fires, and other disasters have taken root.

“And lack of action on climate change threatens billions of lives and livelihoods.

“Preventing future pandemics has proven useful but it also presents the risk of causing one.

“And recent advances in recent artificial intelligence raise a variety of questions about how to control a technology that could improve or threaten civilisation in countless ways.”

Tolimir/Getty

She then confirmed that the clock remains stuck at 90 seconds to midnight. But despite staying the same as last year, it means humanity is ‘profoundly unstable’ while the above risks remain.

Dr Bronson said: “Make no mistake: resetting the clock at 90 seconds to midnight is not an indication that the world is stable.

“Quite the opposite. It’s urgent for governments and communities around the world to act.

“And BAS remains hopeful—and inspired—in seeing the younger generations leading the charge.”

Alex Glaser, associate professor in Princeton University’s Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, said the ongoing war in Ukraine had ‘overshadowed’ the announcement given how grave a situation it is.

He also said the fresh conflict between Israel and Gaza has played a huge part in the 2024 clock time.

JACK GUEZ/AFP via Getty Images

Professor Glaser said the Israel-Gaza war could lead to a broader conflict in the region ‘involving several nuclear weapon states’.

He said: “It’s against this backdrop that we’re facing a crisis in nuclear arms control.”

BAS says that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine ‘has increased the risk of nuclear weapons use, raised the spectre of biological and chemical weapons use, hamstrung the world’s response to climate change, and hampered international efforts to deal with other global concerns’.